This week we will explore how campaign activity matters in congressional elections. So far our predictions have used factors outside of a candidates direct control like the national economy and their party or individual incumbency status. The role of a good campaign can not be overlooked. This post will deal with television advertising conducted by campaigns in what is called the “Air War.” The data studied is from the Wesleyan Media Project which contains data from 2006 - 2018 on campaign ads for House elections. Today’s topics include ad timing, geographic placement, and the insufficiency of the data to make stable 2022 predictions.

Campaign Ads Timing

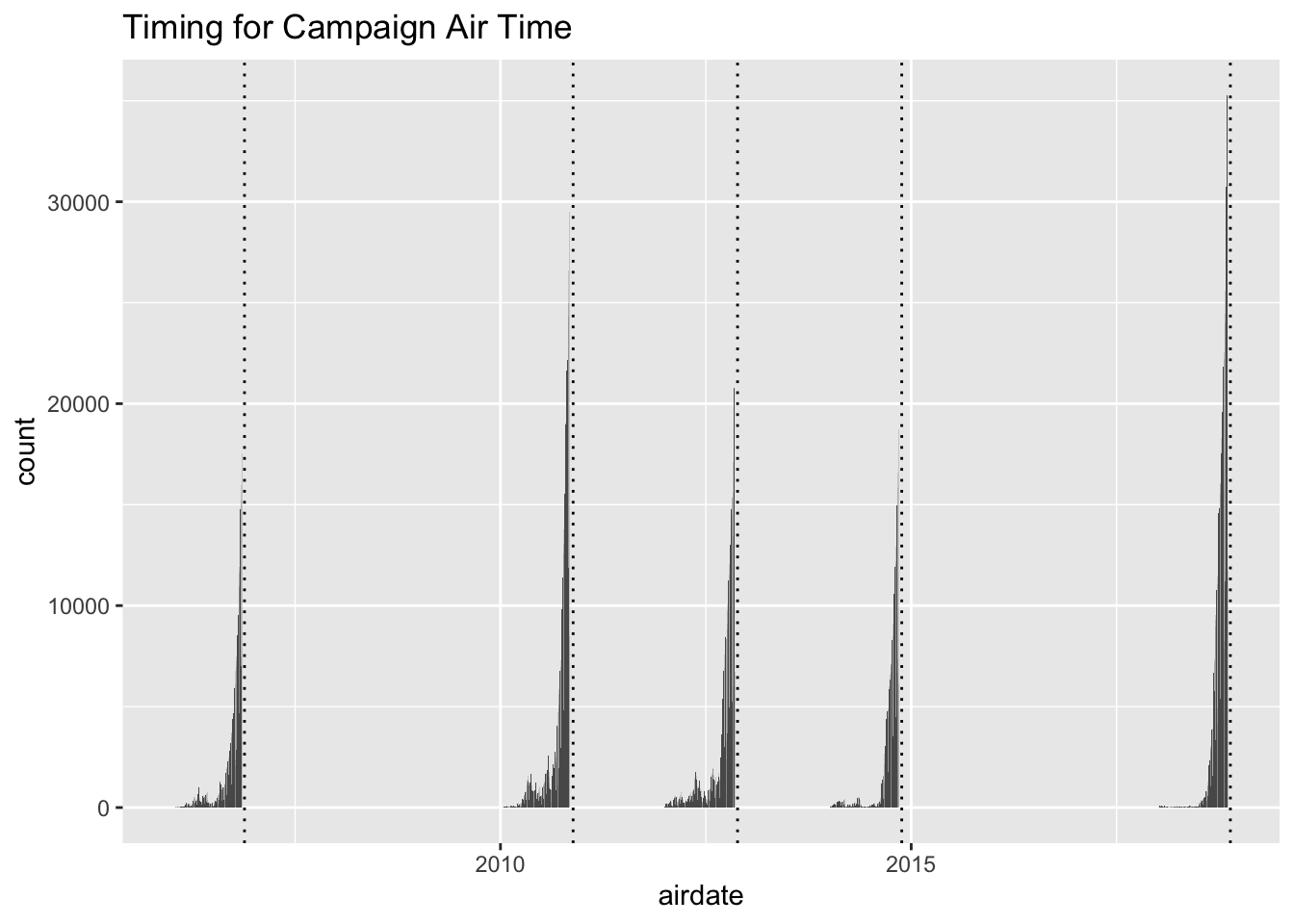

Distribution of campaign ads is something some voters are intuitively aware of. It is no surprise that campaign ads are run only on election years and concentrate to the days before election day. The chart below graphs the ad frequency spikes before each election day represented by a vertical dotted line.

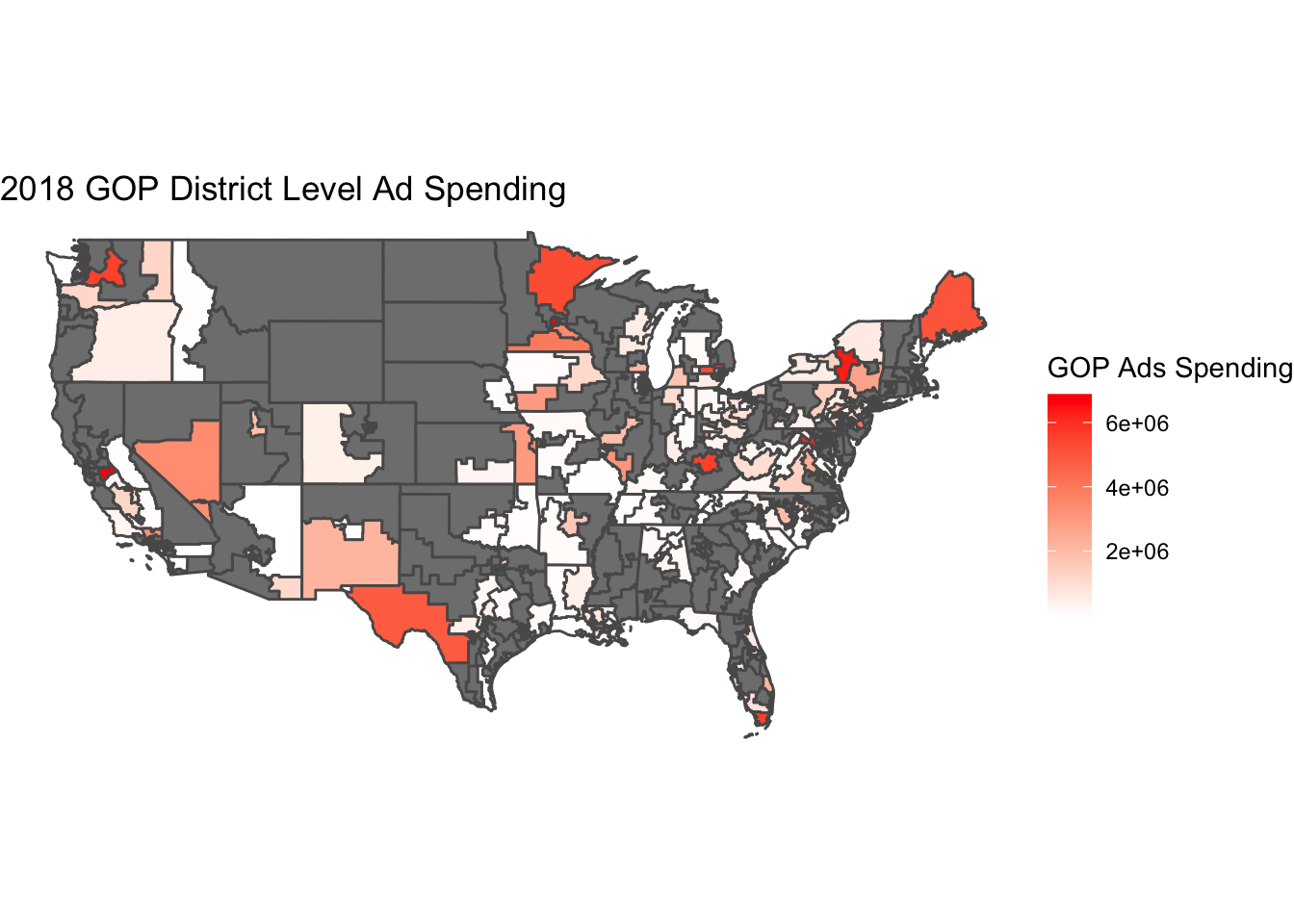

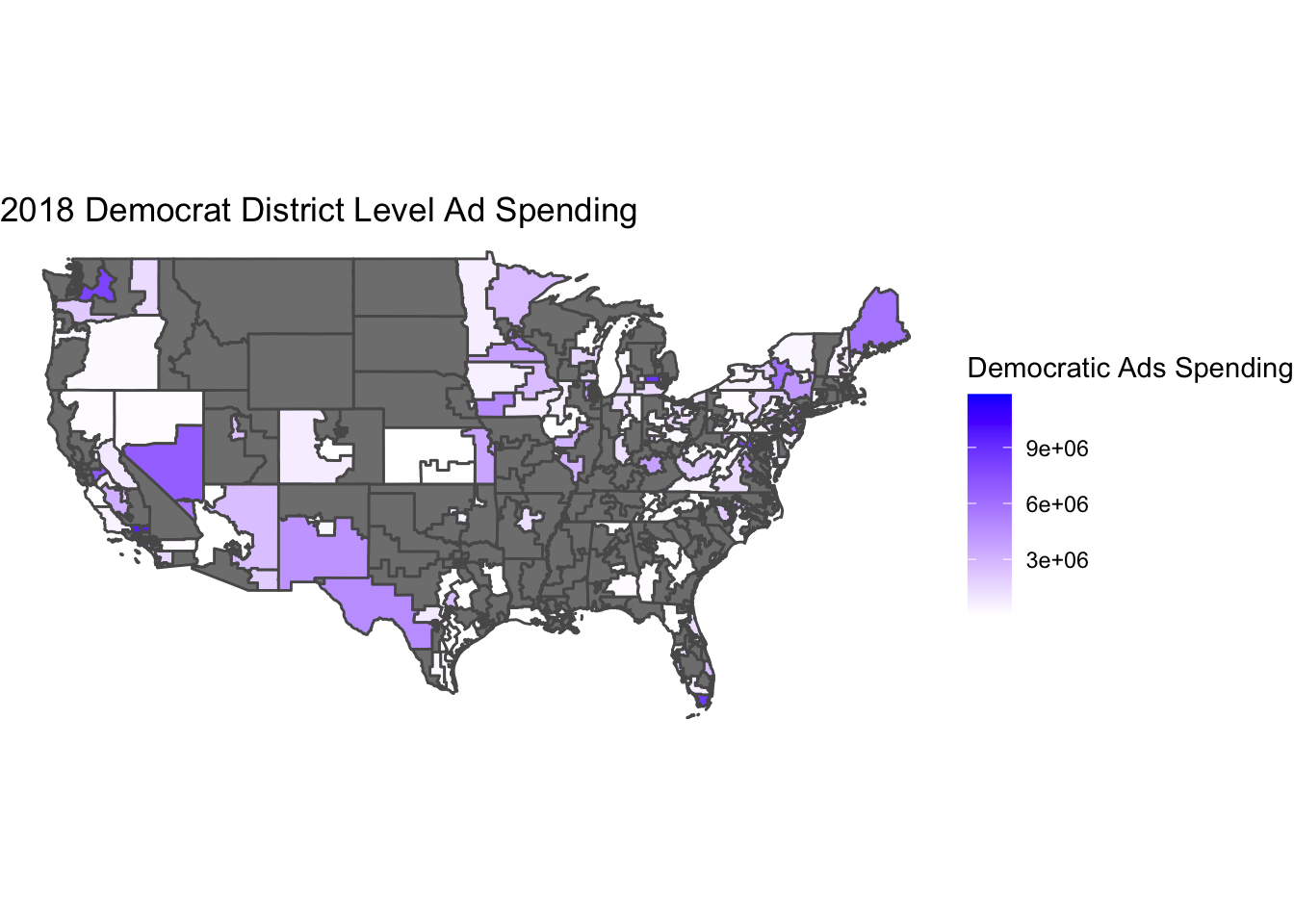

2018 District Level Ads Spending by Party

According to research from Alan Gerber, campaign advertising has a short term effect of voting behavior. We will test whether this effect is present in the spending data from the Wesleyan Media Project. WMP has detailed datasets on the quantity and qualities of congressional campaign advertisements. This includes an estimated cost variable which we will combine for each district in support of either party. The following maps outline party spending volume over the districts. This behavior is well explained by Alan Gerber’s theory that advertising psychological effects last a limited amount of time. Campaigns aim to have their highest visibility right before a person casts their vote so that the ad’s message is fresh in their mind when making a decision.

Ads Spending Models by District

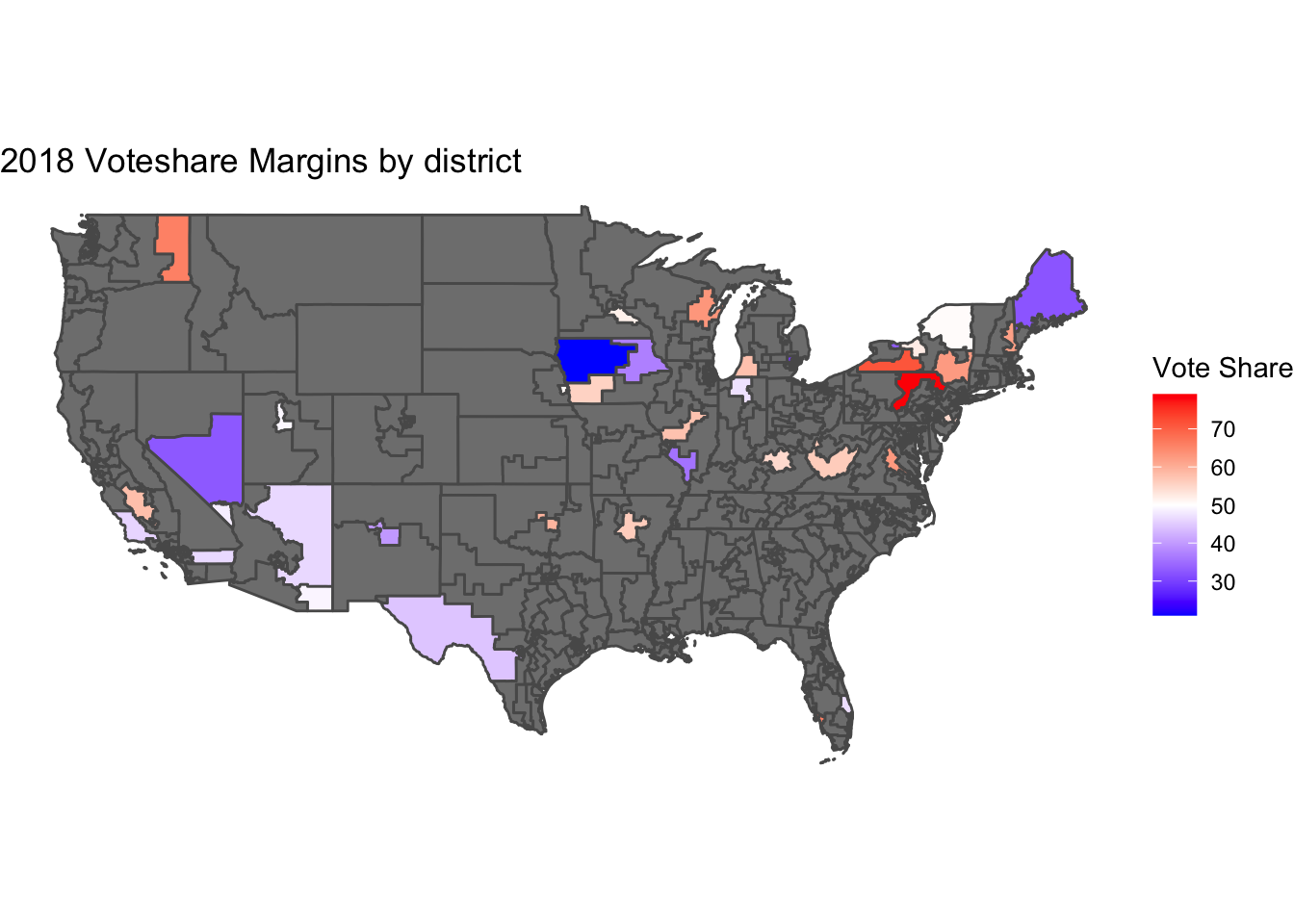

Using the 2018 data as an input lets use historical data to create district level models of vote share as a function of partisan media spending.

This attempt to model has several flaws that are evident from this map containing the predictions from each of the district models. First is how few districts had enough regularly intervaled data to train a model that was not rank deficient. The predictions were also very volatile because of the deficient underlying data so many predictions did not have reasonable values. The 2018 actual outcomes differed from these predictions substantially. For these reasons, I chose to leave ads data out of this week’s combined model.

Creating a New Combined Model

Despite containing millions of observations, this weeks data on advertising turns out to me much more sparse in its range and predictive power because it does not span a large time range and has small coverage over the districts. There is also a lack of advertising data for the upcoming election so there wouldnt be anything to input for a 2022 prediction anyway. So to wrap up a combined model, the available coefficients are fundamentals, polling, and incumbency.

Using - Percent change in RDI - Reelection coefficients - Presidential party incumbency - District polls Leaving out for lack of 2022 data: - Ad expenses

The data is only sufficient to generate models in states where recent and historical polls have been conducted. Out of the 57 viable models, 33 outcomes anticipated a Republican victory while 24 predicted a Democrat victory.

The result table is as follows:

| state | district | pred |

|---|---|---|

| Arkansas | 2 | 67.07 |

| California | 49 | 43.58 |

| Colorado | 3 | 54.19 |

| Florida | 16 | 60.61 |

| Florida | 27 | 46.92 |

| Illinois | 6 | 46.42 |

| Illinois | 14 | 47.50 |

| Indiana | 5 | 56.76 |

| Iowa | 3 | 48.88 |

| Iowa | 4 | 51.71 |

| Kansas | 1 | 68.15 |

| Kansas | 2 | 96.37 |

| Kansas | 3 | 45.04 |

| Kansas | 4 | 86.56 |

| Kentucky | 6 | 94.78 |

| Maine | 1 | 50.08 |

| Maine | 2 | 49.90 |

| Minnesota | 1 | 51.63 |

| Minnesota | 2 | 47.24 |

| Minnesota | 7 | 108.35 |

| Missouri | 2 | 60.13 |

| Nebraska | 2 | 59.70 |

| New Hampshire | 1 | 45.66 |

| New Hampshire | 2 | 53.59 |

| New Jersey | 2 | 52.93 |

| New Jersey | 3 | 49.34 |

| New Jersey | 7 | 47.45 |

| New Mexico | 1 | 38.05 |

| New Mexico | 2 | 49.07 |

| New Mexico | 3 | 41.32 |

| New York | 11 | 46.76 |

| Ohio | 1 | 61.65 |

| Ohio | 12 | 83.06 |

| Oklahoma | 1 | 66.09 |

| Oklahoma | 5 | 49.30 |

| Pennsylvania | 1 | 85.40 |

| Pennsylvania | 7 | 44.83 |

| Pennsylvania | 8 | 63.78 |

| Pennsylvania | 10 | 64.14 |

| Pennsylvania | 16 | 98.35 |

| South Carolina | 1 | 49.31 |

| Texas | 6 | 54.56 |

| Texas | 7 | 47.47 |

| Texas | 10 | 61.65 |

| Texas | 17 | 57.89 |

| Texas | 21 | 53.39 |

| Texas | 23 | 50.23 |

| Texas | 31 | 72.09 |

| Utah | 1 | 71.22 |

| Utah | 2 | 76.05 |

| Utah | 3 | 76.11 |

| Utah | 4 | 49.87 |

| Virginia | 2 | 48.88 |

| Virginia | 5 | 48.83 |

| Virginia | 7 | 49.02 |

| Virginia | 10 | 43.80 |

| Wisconsin | 1 | 59.35 |

References

Alan S Gerber, James G Gimpel, Donald P Green, and Daron R Shaw. How Large and Long- lasting are the Persuasive Effects of Televised Campaign Ads? Results from a Randomized Field Experiment. American Political Science Review, 105(01):135–150, 2011.

Gregory A Huber and Kevin Arceneaux. Identifying the Persuasive Effects of Presidential Advertising. American Journal of Political Science, 51(4):957–977, 2007