There is no better gold standard for election prediction that a direct and simple poll. If you want to know the outcome of a vote, sample a part of the outcome and extrapolate the microcosmic results to the larger population. Yet polling is subject to lots of errors associated with temporal and psychological factors. Gelman and King highlight these problems in their 1993 paper stating that early polls are unrelated to the eventual outcome of an election. This has to do with poll measuring unformed and uninformed opinions on voter candidate preferences. Most voters are not actively seeking information related to far out elections. According to Gelman and King, voters only express their voting preferences later in campaigns around the time when the election is salient and they are forced to make their actual vote. Predictive polling data is therefore only present in the most recent weeks before election day and polling is therefore much less helpful than anticipated because its fruitful results come too late to be effectively acted upon.

Lets investigate how professional election forecasters Nate Silver and Elliott Morris use polling data to generate their predictions for midterm elections.

Silver (2022)

Representing FiveThirtyEight, Silver’s prediction strategy is multilayered and complex.

- Aggregate as many polls as possible while adjust each one

- Likely voter adjustment: Weights a poll based on demographics about whether likely voters tend to be more Democrat or Republican

- Timeline adjustment: Factors in trends over time to infer current poll results from the change over time of previous results

- House effect adjustment: The model assumes that polling errors in historical races are correlated with current error and use that to tweak polling results if a certain poll shows consistent bias

- Use poll from similar districts to infer polling results in districts that are not polled

- Weight polling outcomes with fundamentals model predictions to create a final prediction.

Morris (2020)

Morris’s Economist article provides much simpler but essentially similar approach to prediction.

- Daily updates with newest poll data

- Combined “fundamentals” models that factor in variables like incumbency and partisanship

Across both prediction methods, each strategy incorporates poll and fundamentals in a weighted combo to predict outcomes on the district level. Both strategies then do probabilistic analyses to calculate expected seat share for both parties. And finally, both predictions involve running thousands of simulations with each of their probabilities to map out a normal distribution of outcomes and see in how many simulations each outcome was observed. The strengths of Silver’s model is that in integrates a larger diversity of information sources into its prediction. Morris’s model on the other hand sacrifices additional sources of inference for the strength of greater simplicity. I think that simplicity in a model is also important because it allows a viewer to understand how each variable more directly impacts the outcome. This allows insights to be drawn and acted on. For example, a campaign manager could plan the next campaign steps based on which modeled variables benefit their voting goals. The benefit of simplicity is the same reason its not the best idea to apply machine learning to modeling elections and being none the wiser about why the models predicts a certain outcome. Silver’s model is far from the black box complexity of ML though so on balance I think the FiveThirtyEight model is slightly better than Elliott Morris’s model.

The remaining portion of this post will be to make a combined polling and fundamentals prediction of the 2022 election national seat share outcome.

A CPI Fundamental Model

To start off we can make a CPI based model. The independent variable here is the yearly increase in CPI while the dependent variable is the two party seat share for the incumbent party of each election year. We can visualize past election results and the linear model fitting the trend in the graph below:

##

## ===============================================

## Dependent variable:

## ---------------------------

## seat_share

## -----------------------------------------------

## cpi_change -0.004

## (0.005)

##

## Constant 0.575***

## (0.019)

##

## -----------------------------------------------

## Observations 36

## R2 0.025

## Adjusted R2 -0.004

## Residual Std. Error 0.065 (df = 34)

## F Statistic 0.863 (df = 1; 34)

## ===============================================

## Note: *p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01 We can notice a weak negative correlation between cpi increase and incumbent party seat share. Here the incumbent party is measured as the party with the plurality of the pre election incumbent representatives.

We can notice a weak negative correlation between cpi increase and incumbent party seat share. Here the incumbent party is measured as the party with the plurality of the pre election incumbent representatives.

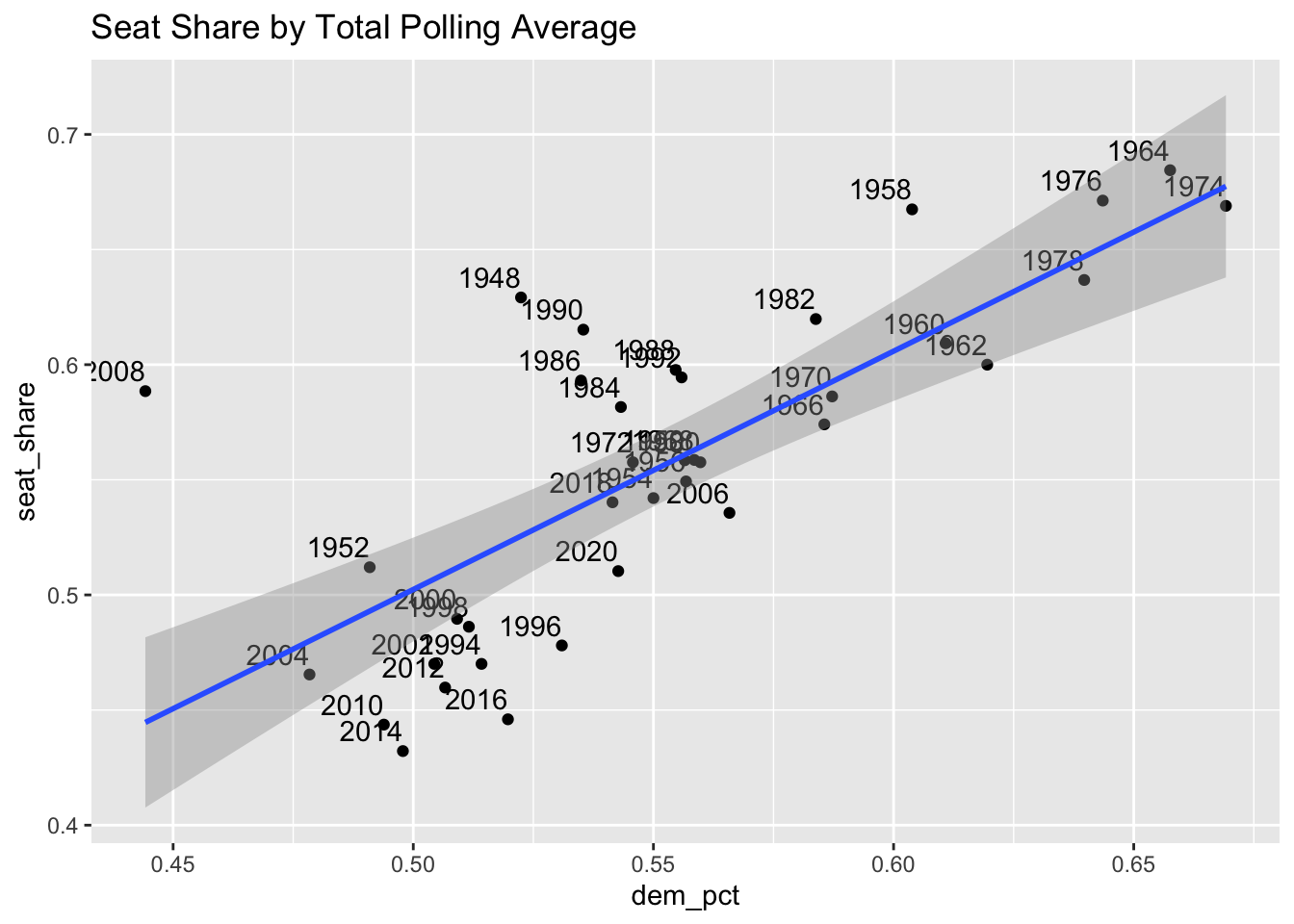

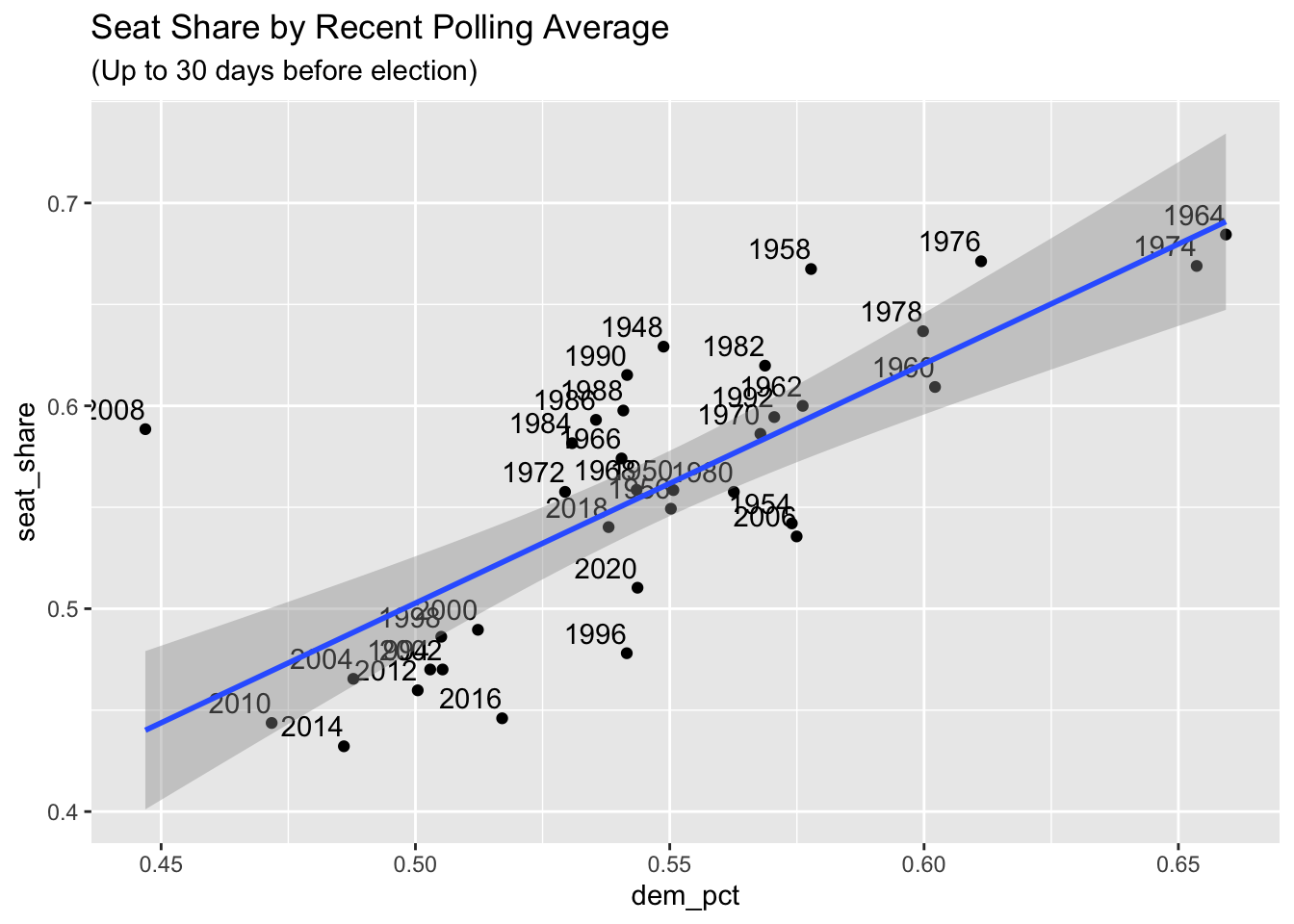

Polls: Total vs. Recent

The polling model I intend to create tests the theoretical observation that early polls are not effective at election prediction. My methods are to take generic ballot poll averages leading up to elections and see how their prediction of the two party vote seat share lines up with the true House election results from that year. The total polls version averages all polls taken up to a year before the election date and the recent polls version of the model only looks at polls within the last 30 days of the election date. I fit a linear model to each dataset and plot the results below:

Total Polling Model

##

## ===============================================

## Dependent variable:

## ---------------------------

## seat_share

## -----------------------------------------------

## dem_pct 1.035***

## (0.153)

##

## Constant -0.015

## (0.085)

##

## -----------------------------------------------

## Observations 37

## R2 0.567

## Adjusted R2 0.555

## Residual Std. Error 0.047 (df = 35)

## F Statistic 45.853*** (df = 1; 35)

## ===============================================

## Note: *p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01Recent Polling Model

##

## ===============================================

## Dependent variable:

## ---------------------------

## seat_share

## -----------------------------------------------

## dem_pct 1.180***

## (0.176)

##

## Constant -0.087

## (0.096)

##

## -----------------------------------------------

## Observations 36

## R2 0.570

## Adjusted R2 0.557

## Residual Std. Error 0.047 (df = 34)

## F Statistic 44.999*** (df = 1; 34)

## ===============================================

## Note: *p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01Within this dataset it seems that the recent and total models map very closely to one another. They show similar slopes of 1.035 and 1.180 increase in Democratic seat share percentage for ever 1 percent increase in the generic ballot average for the Democratic party. They have nearly identical fit statistics and residual standard error. Next lets apply these historical polling models on current polls for the upcoming 2022 election.

2022 Polls

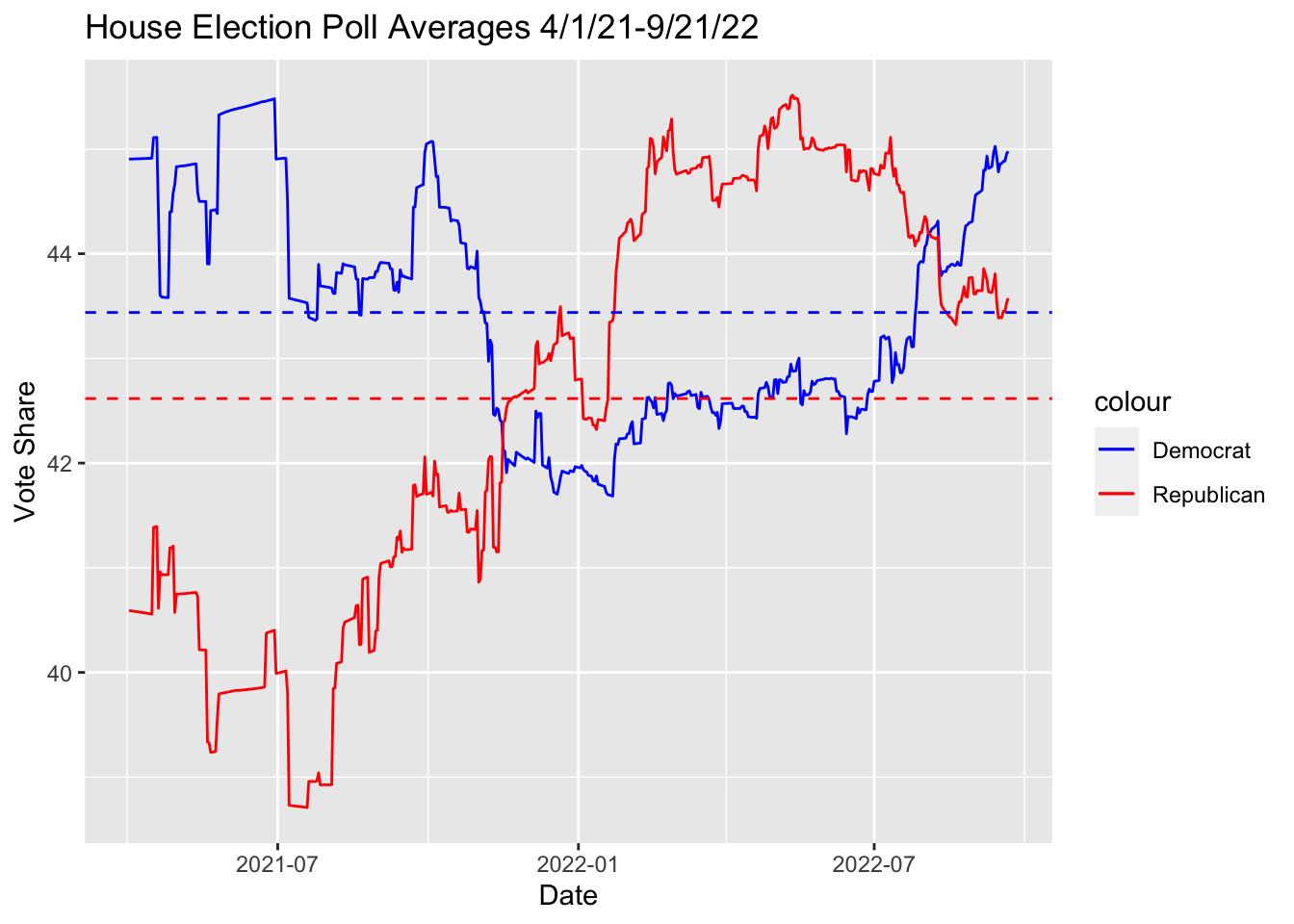

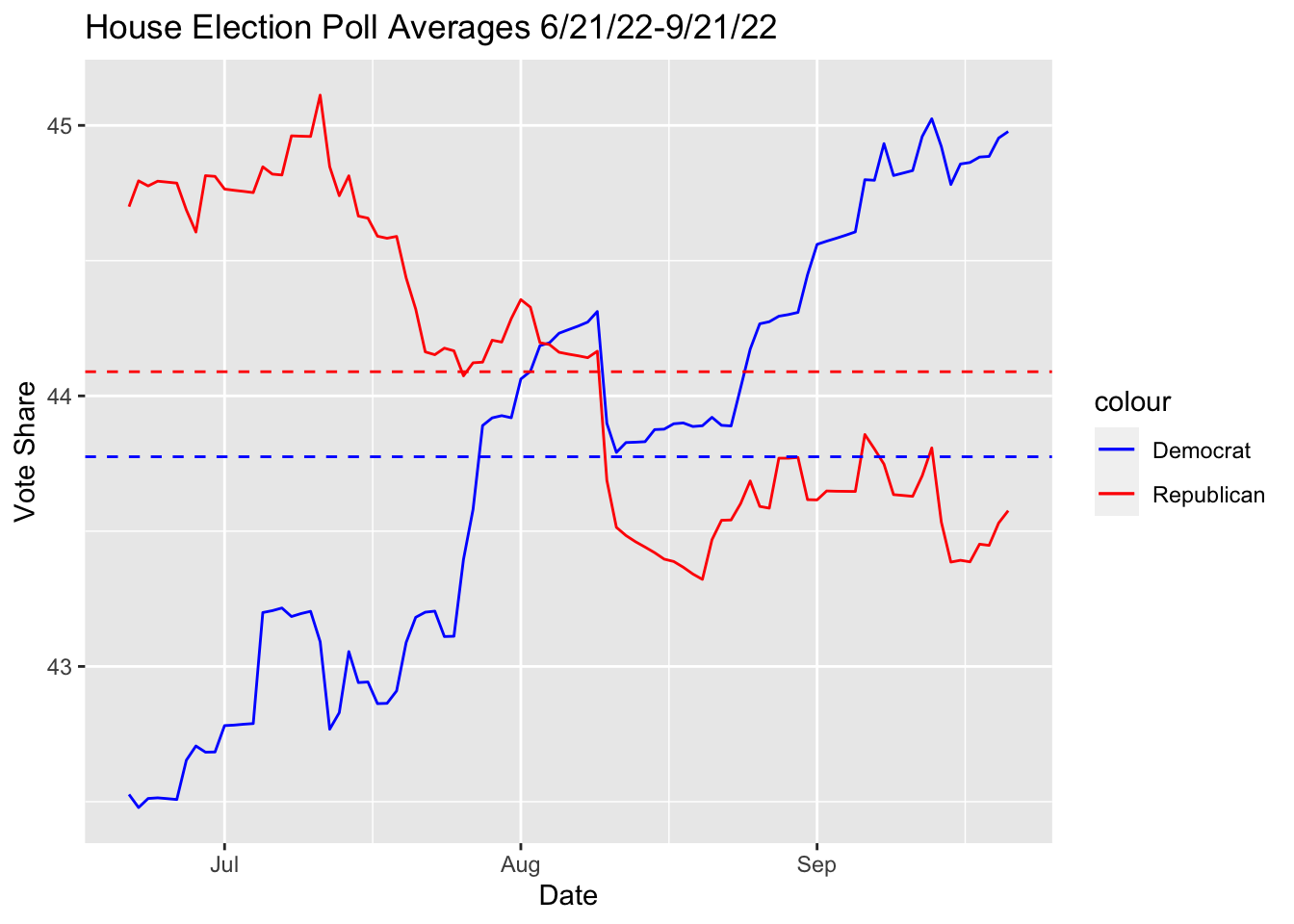

For reference, here are the polling average differences for 2022 generic ballot polls for total and recent time frames:

Lets use these democrat vote share averages in our model to predict seat share in 2022. For simplicity let’s only use the recent polling data model since it shows marginally better fit than the total one.

## [1] "Total 2-Party Average: "## 1

## 0.5086297## [1] "Recent 2-Party Average: "## 1

## 0.5006205## 1

## 0.5018243What a close call! Despite the lower recent polling average for Democrats, the model still predicts a close call with either the total and recent polling averages. Giving preference to the recent data, and combining with the CPI prediction model on 2022 CPI levels at equal weighting, the final prediction of the polling model is a nearly perfect 50% split in house seats: 218 Democrat seats and 217 Republican seats.

References

Andrew Gelman and Gary King. Why are American presidential election campaign polls so variable when votes are so predictable? British Journal of Political Science, 23(4): 409–451, 1993

G. Elliott Morris. How The Economist presidential forecast works, 2020a

Nate Silver. How FiveThirtyEight’s House, Senate And Governor Models Work, 2022